THE BRUTAL killing of Fr. Richmond Nilo last June 10 has added to the toll of slain clerics in the country, a trend that could grow until the Church shows rage against impunity.

Nilo, the parish priest of St. Vincent Ferrer Parish in Zaragoza, Nueva Ecija, was killed by unidentified gunmen as he was about to celebrate Mass inside the Nuestra Señora de la Nieve Chapel in Brgy. Mayamot in Zaragoza. Nilo was the third priest to be slain in six months.

Jesuit Fr. Albert Alejo, a UST alumnus, lamented how priests have become “too focused” on their traditional roles in parishes and other Church-run institutions that they have lost focus on their brethren priests and grassroots communities.

Alejo said this act of tolerance on the impunity also manifests on some clerics’ lack of concern over attacks on democracy and freedom.

“Why is there no rage? Even in parishes where a number of people have been killed, not much reaction emerges. [T]he Church needs to also confess its own contribution to this mess,” Alejo told the Varsitarian.

“Perhaps, we have not really preached the Gospel as Gospel; instead we have burdened the laity with unhealthy parochialism,” Alejo added.

Nilo was set to face Iglesia Ni Cristo minister Ramil Parba in a debate on August 31 at Freedom Park in Cabanatuan, Nueva Ecija. The priest was heavily involved in Catholic apologetics.

A week before Nilo’s slay, Fr. Rey Urmeneta of St. Michael the Archangel Parish in Calamba City survived an attack by two gunmen.

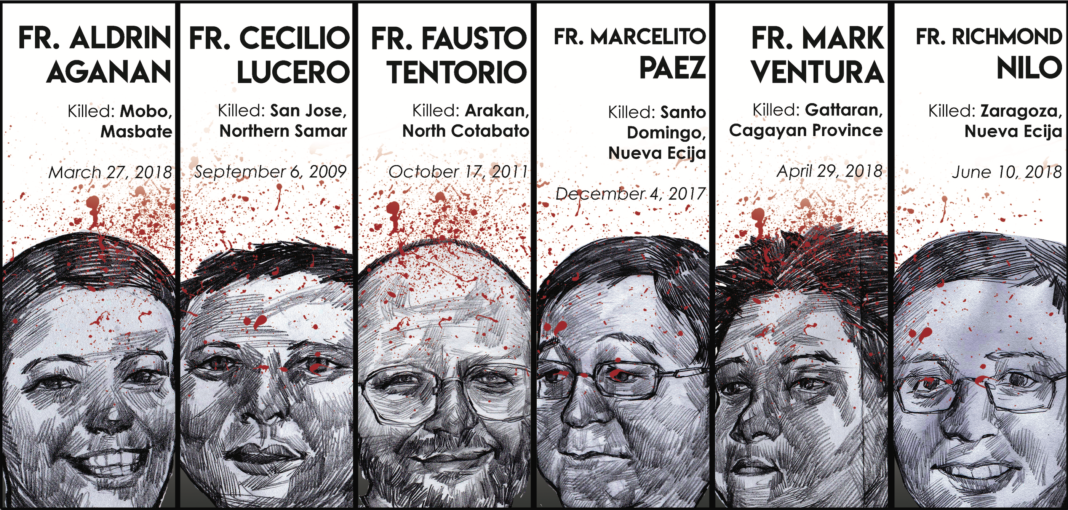

In almost a decade, six priests have been slain in cold blood by armed men.

In March this year, Fr. Aldrin Aganan, a former priest who chose to live as layperson in Masbate, was shot by two unidentified gunmen, who remain at large.

Fr. Marcelito Paez, a retired Thomasian priest and a renowned land reform activist, was shot by motorcycle-riding suspects last December 2017 in Santo Domingo, Nueva Ecija.

Thomasian priest Fr. Mark Anthony Ventura was killed by armed men riding a motorcycle after celebrating Mass in Gattaran, Cagayan, last April 29.

The slay of Paez, Ventura and Nilo came amid criticisms by clergymen of the country’s war on drugs. The police, however, has insisted that these were “isolated cases.”

In 2011, Fr. Fausto Tentorio was gunned down while walking inside the Mother of Perpetual Help Parish compound in North Cotabato. Samar native Fr. Cecilio Lucero was caught in an ambush by an armed group of men in 2009.

These priests, according to Diocese of Malolos Judicial Vicar Fr. Winniefred Naboya, were slain because of their mission to serve the poor and oppressed in small villages in distant parts of the country.

“[These priests saw] Jesus in the persons of the poor and afflicted, and [found it to be their mission to be] always in their defense and protection,” Naboya said in an interview with the Varsitarian.

Naboya said most of these priests were killed due to their involvement in environmental concerns, land reform, oppression of the poor and land-grabbing.

Their memories, however, were blackened by unconfirmed reports from the government that they were involved in corruption and womanizing.

Media reports meanwhile claimed that Lucero, Paez and Aganan’s killings were politically motivated because of the people they were working with.

According to a 2008 report by Olongapo City-based human rights group Preda Foundation, Lucero was linked by former president Gloria Macapagal-Arroyo with the Communist Party of the Philippines.

Arroyo reportedly referred to Lucero as “that communist priest” in a speech at a military ceremony at the Catubig Bridage of Samar in June 16, 2008. Prosecutors, however, dismissed the murder case for lack of substantial evidence.

In line with his work as a land reform activist, Paez assisted last year in the movement to release political prisoner Rommel Tucay, the organizer of militant group Alyansa ng Magbubukid sa Gitnang Luzon, who was reportedly arrested by armed men who presented themselves as soldiers.

Aganan, who was relieved of priestly duties a few years prior to his death, served the remainder of his life as political adviser and campaign manager of politician Narciso Bravo Jr., who belonged to a powerful political clan in the first district of Masbate.

Ventura and Tentorio were both anti-mining advocates and were known for their work in the indigenous communities.

Ventura’s slay was attributed by no less than Duterte to his “illicit affairs” in a May 21 speech during the town fiesta of Tabogon in Cebu, where he showed a matrix with a title page that read, “Shooting to Death of Father Mark Anthony Ventura.”

Police have yet to report any progress on their investigation into these cases.

‘Killing priests unchristian, un-Filipino’

Lingayen-Dagupan Archbishop Socrates Villegas and the diocesan clergy slammed the killing of Nilo and other priests in the country last June 11, saying that killing is “not Christian and not Filipino.”

“Killing is a sin. It is all wrong. This is not Filipino. This is not Christian… The earth, soiled by the blood of Father Mark Ventura, Father Tito Paez, and Father Richmond Nilo, is crying,” the statement read.

“God’s justice be upon those who kill the Lord’s anointed ones. There is a special place in hell for killers. There is a worse place for those who kill priests,” the statement added.

Villegas and his fellow clerics urged Duterte to stop the verbal attacks on the Catholic Church as such kind of persecution “can wittingly embolden more crimes against priests.”

Davao Archbishop Romulo Valles, Catholic Bishops’ Conference of the Philippines (CBCP) president, said the CBCP was “deeply saddened and terribly disturbed that another priest was brutally killed.”

“We strongly condemn this outrageously evil act!” Valles said in a statement released last June 11.

The Archdiocese of Lingayen-Dagupan declared June 18, the ninth day since the killing of Nilo, as a “Day of Reparation.”

Arming priests

With the recent killings of clergymen, Philippine National Police Chief Oscar Albayalde said last June 12 that the police was willing to arm priests.

“If they request it and if we think that there are threats to their lives, we will assist them to go through the [licensing] process for them to feel safe,” Albayalde said in a press conference.

Valles said there was no need to arm priests, stressing that priests are “men of peace, not violence.”

“We are men of God, men of the Church and it is part of our ministry to face dangers, to face deaths if one may say it that way. But we would do just what Jesus did,” he said in a radio interview with Manila Archdiocese-owned Radio Veritas.

Cebu Auxiliary Bishop Oscar Florencio, who is also the apostolic administrator of the Military Ordinariate of the Philippines, echoed Valles, saying the proposal would lead to “chaotic” consequences and solve nothing.

With the absence of rules on the safety of priests under Canon Law, the Church relies on the state.

In a press conference last June 8, Fr. Jerome Secillano, executive secretary of the CBCP public affairs committee, said the state holds the foremost responsibility of protecting priests as they are also citizens.

The Code of Canon Law of 1983 only states that whoever harms or uses physical force against a member of the ecclesiastical authority or a cleric receives a “just penalty.”

Canon Law is limited to “spiritual penalties,” said Naboya. The ultimate penalty imposed by the Catholic Church on persons or clerics who assault a Pope, bishop or priest is excommunication.

“The only recourse that we have is the law of the land and bring these abuses against the clergy to the court of justice,” Naboya explained.