The Varsitarian’s photographers documented different situations of hope and solitude during the Covid-19 pandemic.

Read their stories here:

Renzelle Picar, 19, Laguna

Box

Almost everyone is familiar with the phrase “to think outside the box.” Especially fine arts students. Every week we needed to come up with and present compelling concepts. However, our works should not only be about the beauty of ideas, but also about their appeal and comprehensiveness to our target audience. Our choice of materials and rendering processes played a big role in making a good and concrete visual of the message we wanted to communicate.

But what if there’s a lack of resources to do so? Due to the spread of Covid-19, art supply stores were closed. While many of our plates could be done digitally, some still needed to be done manually. This was a challenge to our creativity and resourcefulness.

One of the plates we needed to do in the traditional manner was collagraph printmaking. I’d like to discuss the process I went through because this was where I mostly tried to look for ways to improvise.

We were tasked to find objects with texture and glue them on a cardboard or something sturdier than bond paper. I collected leaves, lace fabric from an old bralette, tissue paper, grains of rice, eggshells and aluminum foil. It was a relief that this plate did not require a lot of art materials, just objects found in the household.

I neatly cut portions of a box of baby milk and designed and glued the objects on them. The next step was to put some paint. I used black and brown acrylic paint to have an antique vibe on the print.

Since I did not have vellum paper left and I did not trust how well bond papers absorbed paint, I cut portions of another box and mounted sketchpad paper on them. I then placed the matrix on top and used a plastic bottle full of water as a rolling pin to finally get on with the printing process. With some pressure on the bottle, the texture of the objects covered in paint was imprinted on the paper.

During the first semester of my sophomore year, my design theory instructor, Mr. Raphael Kalaw, told us he did not agree with the idea behind “thinking outside the box.” He said it was better “to think inside the box” because true creativity shows when one lacks the resources. I think what he meant was that it was good to have exceptional and out-of-this-world ideas, but one must also learn how to bring them to life even if there were no materials to work with. Despite the lack of resources, I was still determined to finish my plates so I won’t be marked “In Progress” or INP.

The improvisations I did made me realize that I was lucky enough to finish the plate. As a member of a middle-class family, I still happened to live a comfortable life. Yes, certain necessities were in shortage, but my family did not suffer. I could only imagine what it was like to be a student living in areas where the quarantine was strictly imposed, and in households where there was hardly any material that could be repurposed for a plate.

In times like this, creativity, when put into good and more sensible use, can be an instrument of survival. Creativity is viability.

Jean Gilbert Go, 20, Chiang Rai, Thailand

At a university dormitory in Chiang Rai, Thailand, exactly 1,407 miles away from home, I was locked in isolation. With Covid-19 on the loose, my group, three Filipinos and a Vietnamese student, really had no choice but to stay inside a small room.

Before things got worse, I was an exchange student at Mae Fah Luang University. During the day, we got to experience using advanced equipment in chemical laboratories, and it was everything a food technology student like me could ever want. After class, I spent my free time eating out at night markets and exploring what Chiang Rai had to offer. Every day was a new experience: new food, new sights and new friends. Everything went well, until the virus rendered everything to a sudden halt.

Classes were held online, shops were closed, and safety measures were strictly implied. The quiet province of Chiang Rai became even more silent. The university took immediate action; the semester didn’t end, but it was cut short. Enrollment and dormitory fees were cut by half, and there was free and unlimited internet for all. Surprisingly, the professors were also very considerate toward their students. This sudden shift of balance made me afraid, nay, terrified. Thailand’s governance, while not perfect, somehow gave us comfort. Without the use of unnecessary force, they handled the situation better than the Philippines did.

And it was really sad to think that I felt safer under a government that was not my own.

This did not make me complacent, however, because of fact that all my loved ones and my fellow countrymen back in the Philippines were unsafe from the virus.

Every time my mother called me through Facebook messenger, she always ran down a list of what I needed to do to avoid contracting the virus. She always told me how concerned she was for me and my situation, but I always reassured her that I was doing well, and I always told her that they should worry about themselves more considering it was tough living in the Philippines, especially during this crisis, wherein citizens had no choice but to help each other out.

Being far away from loved ones was only one of the many difficulties of a person quarantined away from their home countries. Another one was money. It did not come by easily, with workers barely getting any pay due to businesses being abruptly shut down. A lot of people were affected. So were my parents, the only people who could send me money. Being indirectly affected by the loss of income, I tried to save my allowance from the last month by buying food once a day, a skill I had learned as a student.

Food is a cheap necessity here in Thailand, so it is not something I should normally worry about. But spending less felt like a job I could do to help my parents. During lunchtime, I would buy the cheapest meal at a canteen a few steps away from my dormitory, and at dinner time, I cooked a pack or two of instant noodles. On good days, we pitched in money for ingredients so our Vietnamese roommate would cook for us. It would cost more than my daily meal, but I would end the day with a full and satisfied stomach.

I was unable to go home for my birthday. I stayed in the corner of my dormitory room, slurped instant noodles and played video games as a coping mechanism. It might not be as bad as it looked like, but the feeling of being away from my family, amplified by the constant fear for their state, made the moment gut-wrenchingly sad.

I was not the only one in this position. There are probably millions of students far from their families, and even the OFWs who could not close their eyes without seeing their loved ones behind the blackness of their eyelids. Despite the direness of the situation, I believe we will rise from all this. We will get to hug our loved ones once again. We Filipinos are extremely resilient. Whether a deadly virus or a deadlier government, we will stand and see the sun once more.

Camille Torres, 19, Quezon City

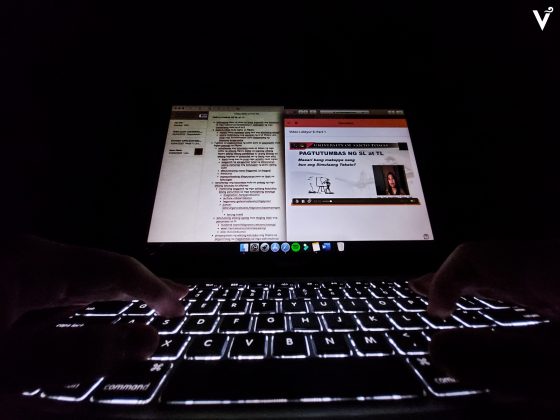

The show must go on for journalism sophomores as we continue to engage in an online classes amid the Covid-19 pandemic.

It was late in the afternoon of March 9 when classes in Manila were suspended amid the pandemic, and the Office of Secretary General advised faculty members to use the UST Cloud Campus online facility for instruction. I asked myself so many “what ifs,” and several thoughts raced in my mind. Nonetheless I made myself preoccupied with online classes.

Our journalism classes included discussions of how journalists and media practitioners are considered frontliners as well. Professors encouraged our class to disseminate factual and credible information on social media, to help people make informed choices during this crisis.

History repeats itself

More than a thousand Facebook accounts shared Dominican Vocations’ retrospective post on what happened in UST during Academic Year 1942 to 1943, the height of World War 2.

“The first school year (1942-1943) during the Japanese occupation started on June 15. Thus the year 1942 saw the continuing academic activities in UST largely constrained by the war,” the social media post read.

The University back then could only operate the ecclesiastical faculties of Theology, Canon Law, and Philosophy, the Faculty of Medicine and Surgery, and the College of Liberal Arts.

Our battle against this pandemic shows that our experiences are somewhat similar with wartime students. Future journalists must be brave and intrepid, after all.

Like in a traditional classroom, professors did not only give lectures but also asked us about our situation. Some of them asked how our local governments took action and how we have coped since the start of quarantine.

With a lot of events happening, some finished that minimum 1,000-word pandemic essay in less than 24 hours.

Nadine Deang, 20, Las Piñas

From a distance

Family members were supposed to be stuck with each other during this pandemic. Not so in my case, an only child used to living with just two people: my mom and dad.

In late February, before the “enhanced community quarantine” or ECQ, my mom was rushed to a hospital in Quezon City due to cardiomegaly or an enlarged heart. She was discharged a week before the lockdown.

After being discharged from the hospital, my mom had to stay with my aunt to recuperate, since both my dad and I were usually out the whole day because of work and school, respectively. She has not returned home since.

The past two months have been really hard for me because I missed my mom often, but I did not have a choice. My mom was always my go-to-person since I was young. Because she was not around, I found myself having a hard time coping. She was not here physically to console me at times when I needed it the most. By phone, we have been talking to each other. trying to fight our daily struggles.

The Covid-19 lockdown gave my mom things to ponder about and made her realize some things.

“I never thought that it could really happen to me and to my family. Being away from home was not my choice. Instead it was a situation that left us with no options,” she said in a phone call.

“Although I was discharged before the pandemic, I have to recuperate in my sister’s house in Quezon City since my husband and my daughter were not always home because of work and school,” she said.

The last time we saw each other was when she was rushed to the hospital. I was with her while she was going through hospital procedures.

She was caught off guard, since she was the type of person who was always prepared for anything. This one was an exception.

“On the other hand, I was so proud of my daughter because she really had the courage to deal with the situation, as she was the one who dealt with the doctors and contacted the family,” she said.

This was the first time in my 20 years of existence that we were apart for this long. Though the distance kept us apart and the communication barriers were thick, we still found ways to connect our dots with one another and fill in the gaps.

We call each other more often than before. It made us even closer. No matter how far we are from each other, we will always find our way home.

“Home is where your heart is and for me that is with my daughter, Nadine,” she said in a phone call.

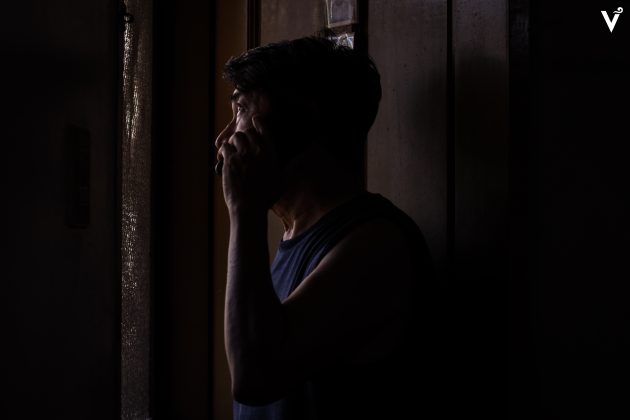

Marvin John Uy, 19, General Santos City

They say, “Being brave is not the absence of fear, but the action in the face of fear.” As a child of a healthcare worker, I could not help worrying about my mother whose work entails the danger of exposure to Covid-19. She has been a physician for almost 27 years, and never have I been worried about her work until these past few weeks.

As the Philippines enters its third month of facing the pandemic of the novel coronavirus or Covid-19, the number of confirmed cases has reached 14,035, with 3,249 recoveries and 868 deaths as of this writing. A significant number of infections were among health workers.

In a country that was not prepared for a pandemic, the rise in the number of affected healthcare workers was caused by the lack of personal protective equipment or PPEs. PPEs serve as an important line of defense against this disease.

My mother, being hypertensive and diabetic, is more susceptible to severe Covid-19 if infected. Though the cases of the virus in our hometown, General Santos City, is low, with only one confirmed case and no cases of local transmission reported as of writing, my mother is still at risk of encountering asymptomatic persons in her clinic.

To make sure she is fully protected and sanitized every day, she has included new practices in her daily routine. She puts on a face mask before leaving for work and sanitizes herself before entering our home. She has also adopted new measures in her private clinic in the middle of the city, such as screening by phone and accepting patients only by appointment. Wearing a mask and face shield is also a must in her clinic and during hospital rounds.

Having gone home to Mindanao just prior to the declaration of ECQ in Luzon, I spent my first 14 days in home quarantine upon the insistence of my mother. Seeing her putting on her PPE made me anxious about the harsh reality of this “new normal” – that we have an invisible enemy that spares no one.

The world is on edge as it awaits a much-needed vaccine. I have taught myself to calm my mind despite some negative thoughts. This is partly because I have seen the value of the sacrifice of my parents to provide for our needs. This pushes me to maximize my time and resources and finish my degree in engineering. I have dedicated my time to helping her in our household to lessen her stress amid this pandemic.

With the end of this pandemic still uncertain, we realize even more how dependent we are on one another. Resilience and support from our loved ones are more important than ever. We have the ability to address this situation and face this “new normal” as long as we stick together.

Arianne Maye Viri, 20, Rizal

Alone and vulnerable

From online classes, stay-at-home orders and curfews, the thought of self-isolation can be a stifling feeling to anyone, but the level of fear that this invisible threat can bring to seniors living all by themselves creeps to the spine differently. With public transportation suspended and senior citizens having the highest fatality rate due to Covid-19, how can a 78-year-old get through the two-month community quarantine and sustain her daily needs while shunning the risk of infection and having only solitude as her daily companion?

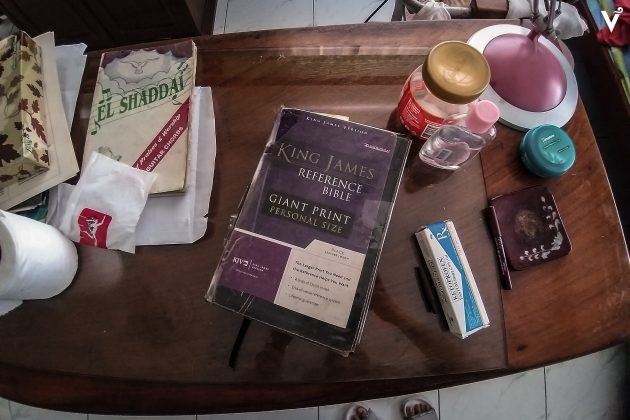

Cresencia (Lola Ising as most people call her) has been living alone in Rizal for almost five years. She never married. Undeterred by age, she continues her passion for service as a post-graduate professor at a Christian university in Manila. Church services and prayer meetings for at least two days every week kept her in high spirits. But in the latter part of March, the regular routine was put on standstill when the local government of her hometown ordered a community lockdown. There were three Covid-positive cases in the municipality.

“Noong walang Covid, it was okay for me to live alone. Kung gusto mo lumabas, makakalabas ka. Pero ngayong may Covid, you cannot do anything. The more you will be lonely [since] you do not have any alternative but to stay at home,” she said with a soft grin and worried eyes.

With private and mass transportation off the table, walking for about 20 minutes to the closest supermarket sounds doable. But with a severe knee condition, Lola Ising will falter in less than a hundred meters.

Lola Ising is extra mindful of her vulnerable state amid the pandemic. She opens the fridge and medicine cabinets to see what is left, writes a list on a sheet of paper and messages her nephew Arnold, who lives 30 minutes away, to buy the items she needs for the week. Arnold has become an avid listener of Lola’s stories, transitioning from her confusions in using FB Messenger to rants about her own foul-smelling garbage bin outside the house. Fortunately, Lola Ising also has neighbors who check on her occasionally.

Small acts of kindness pepper her days. From Arnold’s weekly visits, free medical check-ups by a physician living across the street, to the fact that she remains alive and well despite years of solitude, these little miracles keep Lola’s heart grateful and content.

Living all by herself during a city lockdown is tough, but so is she. Tougher, even. She is headstrong, quick-witted and above all, faithful to Him and His grace amid the pandemic. Instead of feeling blue, she decides to see the silence of isolation as God’s simple way of communication.

“Kailangan maranasan mo talaga `yung pag-ibig ni Lord eh. Kailangan talaga mayro’n kang right relationship with God. You should be close to God and God will be close to you. Yun [ang] pinanghahawakan ko ngayon kahit mahirap,” she said.

Jazmin Tabuena, 22, Rizal

All things are temporary

As I write this, my batchmates and I are supposed to cherish our last few moments in the University, eating in our favorite food spots while reminiscing our college lives and reaping the fruits of our labor. When the “enhanced community quarantine” or ECQ was implemented last March 16, I knew our most-awaited graduation rites would have to be delayed.

My “love language” comes in different forms: touch, tight embraces and a few words to spare. These have been replaced by gloved interactions and midnight video calls. My batchmates and I show each other the food we eat online instead of sharing our baon. These have kept us sane in this pandemic, as we finished our thesis requirements together. It has been a mentally rough experience thinking of all the uncertainties we face, but I am always grateful for my friends.

When I stay away from the online life, I cope with the music my brother plays every afternoon, watch the calming sunset, watch my mother cook, and make a faux disco floor to dance my anxieties away. They have been effective so far.

The previous months were indeed a financial challenge from a student who was eerily shy to ask for allowance from her parents, and made ends meet from personal savings. My printed materials and supposed-to-be coffee table book will probably never see the light of day.

CFAD seniors will no longer have an online defense and everything will be evaluated online. The thesis defense is probably one of the most terrifying moments that we will never be able to experience. I am both thankful and regretful.

The rosary, candles, marker and a special dedication uniform were all set. After five years of study, we were supposed to finally run out of the historic Arch of the Centuries. But I guess waiting a little longer will not be terrible, since staying at home will help our frontliners. “These can wait, our moment can wait,” I said to myself. Our moment now involves helping flatten the curve for the safety of everyone.

The studio that shot our graduation photos notified us in February that our frames were ready for pickup. No one got the frames because of our school deadlines. This was probably a sign that it was not yet time to see ourselves in a toga. For now, I will settle for a self-portrait in my uniform and patiently wait for the day when my parents come up with me on the stage, the Rector turns the tassel, and I can finally call myself a graduate.

In the meantime, I will just relive the years I covered the Baccalaureate Mass for the Varsitarian. We will have our moment too. We will just have to wait a little longer.