OUTSIDE, the sky flashed and cracked, and the rain poured with fierce abandon. My socks were soggy and my leather shoes were wrinkled with creases.

“Thank God, schoolmate! Now you have mine to use,” I murmured to myself, cursing the person who stole my umbrella outside the library.

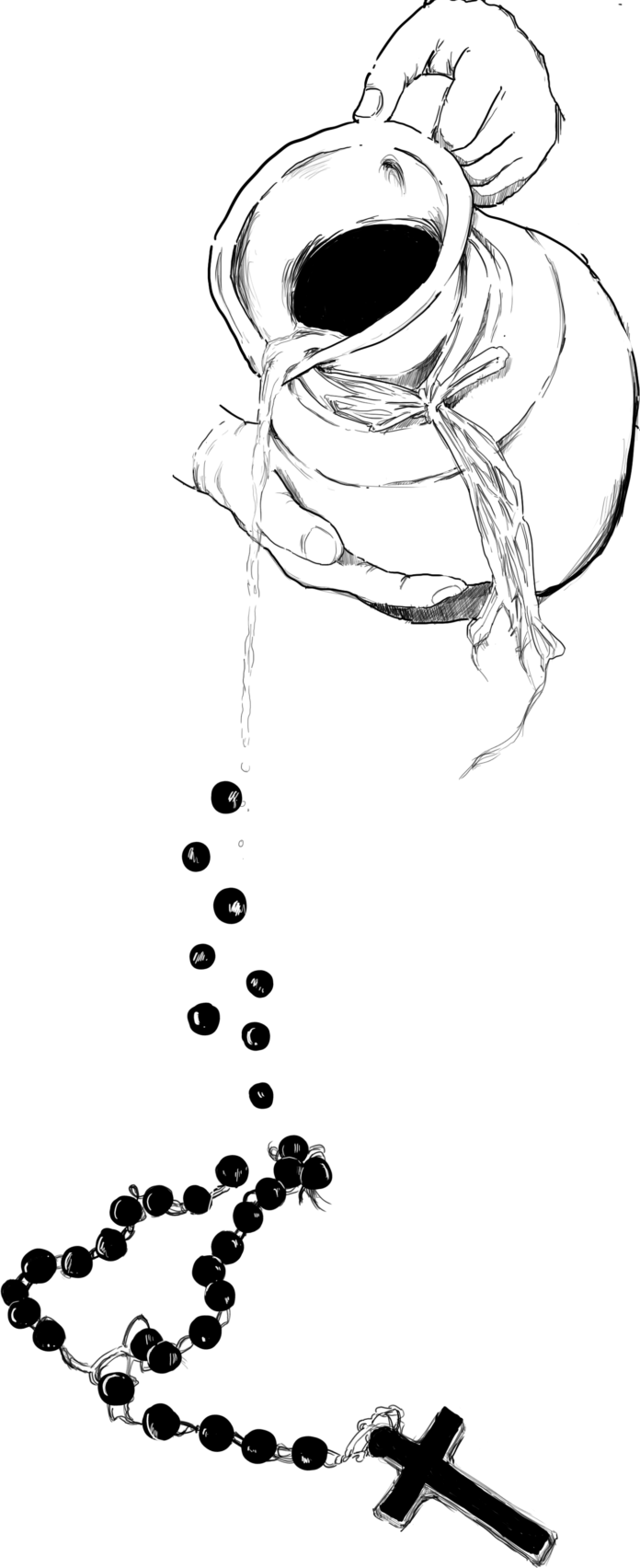

People came and went into the chapel, some of them even taking the time to dip their fingers and make a sign of the cross. I simply opened my bag and inspected the damage: my five-page paper on Medieval poetry was soaked, as was my Algebra worksheet and the history book that I was supposed to return to the library last week.

My shoes squeaked annoyingly, echoing through the now almost empty chapel, save for a hermana praying the novena at the last row and a fellow student desperately trying to mend his umbrella which had snapped in the strong wind.

I settled onto a bench in the third to the last row, suddenly noticing the weather let up a little and a beam passing through a glass pane on the left wing of the chapel. I was suddenly reminded of my tumultuous transition into college, which had become a flurry of ill-defined images strewn together.

My mother, a failed businesswoman approaching forty, found a job as a housekeeper for a wealthy real-estate tycoon in Makati’s lower district.

She left home in the early hours to endure the morning commute and arrive home nearing midnight or later. I sometimes hear her over the phone with her boss, the stoic and often vengeful Mr. Serbal, whose hair-trigger temper rendered her mute and dripping in a cold sweat.

She tried her best not to show any emotion in front of me. She took her calls in her room with the door shut or the bathroom, which ironically amplified Mr. Serbal’s berating─ thunderous and screechy sonic bursts through the phone in a voice that was coarse to the ears.

“Why the hell did you iron my twenty thousand peso suit? Are you some special kind of stupid? And where are the envelopes and folders I told you to take from my file holder? Pray that you have not lost those important documents, or else you will lose your salary and your head!”

Afterwards, she dried her tears and put on a stern expression, or if the mood suits her, a forced smile, as she joined me on the dinner table. I never wanted to ruin those moments, given that they were few and far between.

“Just do your best, sweetheart. Always do your best. I’ll be fine,“ she had always reminded me.

Her only sober moments, when she was not forcing herself up at four in the morning and battling her way through morning commuters, was Sunday mass, which she was intent on attending diligently.

I too picked up on the Catholic upbringing some time later, taking pride in my ability to recite Hail Holy Queen in Latin. It made my mother smile a little.

She told me that I should not refer to Jesus as “Papa” because he was in fact more of a brother. I talked to him as such, sometimes even writing letters for him on notebook pages.

“Buddy, er, brother?” I remember reciting once in prayer one night. “Please─”

I had stopped at the thud that reverberated through the wooden floor. I had rushed downstairs to see my mother frothing at the mouth, her arms flailing and her body convulsing. Dialling with shaky hands and taking shallow panting breaths, until an ambulance arrived an agonizing ten minutes later, I had asked the paramedic why it took so long.

“We were on coffee break,” he had replied with a straight and unabashed expression. My hands had started balling up as I restrained myself from having an outburst, for my mother’s sake.

While the ambulance had buckled and turned on the bumpy, unpaved road, I saw a piece of paper crumpled up in my mother’s hand.

“Luz, take care of Christopher,” it had read. I stuffed it in my pocket and brought out a faded photo of us at a friend’s birthday party when I was six. I slipped it under her arm and waited until the ambulance finally stopped.

While at the emergency room, I was informed by the doctor that she had ingested rat poison and that they were doing their best to flush it out of her system. I was asked to stay the night. A couple of minutes later, my mother’s phone rang.

“Hello? Isabel? ISABEL?” a deep, grumbling voice said. “Where do you think you are? You think it’s your day-off, huh? NO, get your ass up here! I hope you have another way to feed that boy of yours because─”

I ended the call before Serbal could continue. Another five minutes passed, and it rang again.

“Hello? Mrs. Sarmiento?” It was a woman’s voice this time. She introduced herself as a secretary for the Secretary of Finance for my university. I introduced myself as her “close relative.”

“I’m afraid we can longer forego your payments. If Christopher’s debts are not paid, we will no longer allow him to graduate,” she said.

I had ignored everything else she had said and simply slumped down onto the cold hospital floor, not even a squeak escaping from me. My mother was admitted to the St. Andrew’s Ward in Cubao, while, true to her wishes, my aunt Luz moved in with me. I visited my mother often after classes, often finding her in her room spaced out and oblivious.

I prayed. And I did again the next night, and then the next, alone in an empty room or in the chapel just a couple of minutes walk from our home. But as the weeks went by, her conditioned showed no signs of getting better. Her physique had become almost scarecrow-like. She had frequent episodes of spacing out and staring at the picture of St. Francis of Assisi posted in her room.

“I thought you were my friend, my brother…” I once said in prayer. All of these haunted me like poltergeists in search of anguish and blood. My college life became a blitz of trauma and the faint, bitter aftertaste of cheap sari-sari store beer. There was not much point in Sunday mass.

I passed by the university chapel often on my way home. I cursed it often.

That was three years ago.

“Today was a fluke, nothing else,” I thought to myself as the goblets pelted the roof and a gust of wind swept in from an open window. It blew out most of the candles near the chapel door. My phone began to ring.

“Hello? Christopher?” my aunt Luz said. “Are you headed home?”

“Yes, just caught up in some bad weather that’s all,” I replied.

“Well, I am here at the ward. There’s someone here who wants to talk to you.”

There was a moment of silence until I heard a woman’s voice, hushed and cautious almost.

“Hello?” she said, steady and careful, like a toddler tentatively trying out a new word.

“Mom?” I asked. There was another couple of seconds of silence.

“Sorry,” she said. I heard her sob a little. My aunt reclaimed the phone.

“She’s a bit tired now. The doctors say she’s doing well, maybe even well enough to come home one of these days.”

I was in shock. I visited her many times before and each time she sat beside the bed, spaced out in front of the window. I wondered what had changed.

“But Tita,” I said before being cut off.

“Do you remember that picture? That one with you in the balloon hat?” she asked me. I stood there silently.

“Yes. I remember.”

“She keeps it beside her everyday. Some of the nurses can’t get it away from her.”

I still couldn’t utter a word. “She’s doing a lot better now. Maybe one day, she can come home, if she gets well enough.”

“I have to go now, the street will be flooded soon,” I said, saying goodbye, but not before my mother reclaimed the phone again.

“Always. Best,” were all I heard before I finally said goodbye.

The rain outside was still pouring. I laced up my shoes and fastened the straps on my bag. I braced myself in front of the door of the chapel as I spotted a jeepney bound for Balic-Balic. I rushed towards in strides, big splashes trailing me as I lept aboard and turned to see the sky: motionless, silent, settling. Cedric Allen P. Sta. Cruz and Nikko Miguel M. Garcia