THE QUADRICENTENNIAL celebration is a catalyst for new constructions. With the Alumni Center and Sports Complex as multi-million projects, it is gratifying to know that the University recognizes the importance of investing in buildings to further enhance its facilities. Sure, they may be costly but their benefits are long lasting compared with fireworks.

THE QUADRICENTENNIAL celebration is a catalyst for new constructions. With the Alumni Center and Sports Complex as multi-million projects, it is gratifying to know that the University recognizes the importance of investing in buildings to further enhance its facilities. Sure, they may be costly but their benefits are long lasting compared with fireworks.

However, I can’t help but notice that all these structures, when brought together as a complex, fail to fully evoke a “spirit of place.” The phrase refers to the distinctive and unique characteristic of a place, a synergy of its physical environment, interpersonal appeal, and underlying history and culture.

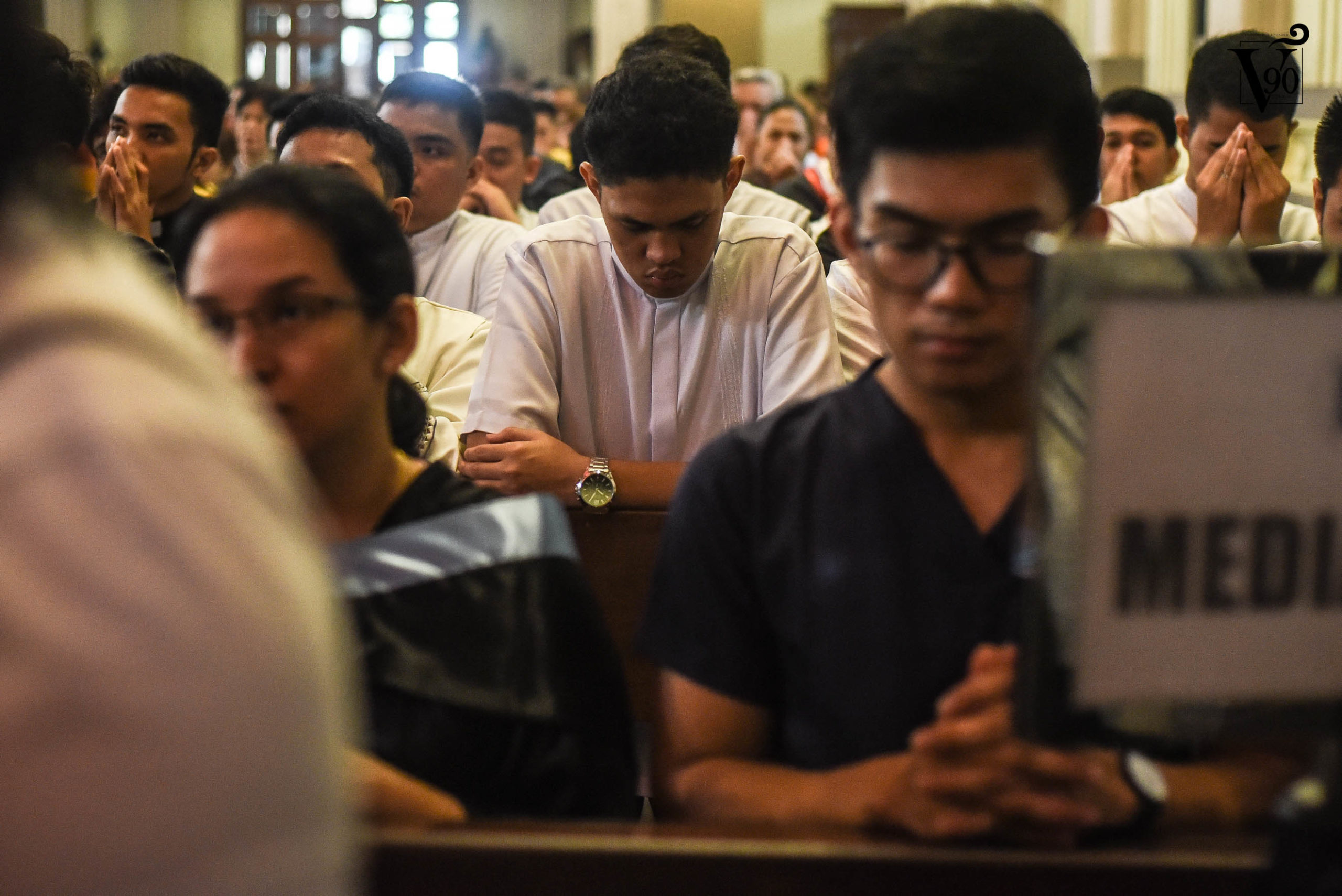

I see nothing wrong with UST’s interpersonal appeal, as the Paskuhan and Quadricentennial festivities have appealed even to the outsiders. The campus also exudes a scholastic aura as students can be seen rehearsing at the Quadricentennial Park or studying at the UST library. The problem lies in UST’s aesthetics on recent structures, which do not exude the history UST wants to share.

The campus has always been known of its Main Building. Its signature tower design has always been a well-known subject for photographs and logos. With the exception of the Miguel de Benavidez Library, the rest of the buildings seem to have paltry aesthetics that fail to conform with the UST Main Building.

“Chopsuey architecture,” as some of our architecture professors call it. The University faces an identity crisis as it fails to come up with a unifying style that can be evident in all of its buildings. Renaissance (Main Building), Art Deco (Santissimo Rosario Parish), Bauhaus (St. Martin de Porres Building), Postmodern (Beat Angelico Building), and International style (Roque Ruaño Building) are just some of the architectural styles employed individually on campus. If all these buildings should narrate the rich history of the University, the story would be full of plot holes and inconsistencies.

The probable justification for the helter-skelter aesthetics is that the University wanted to evoke the popular architectural style at the time a building was built. I beg to differ. What makes buildings truly beautiful is the story behind them. When a building changes its architectural qualities without any compelling reasons, the place will lose its historical significance.

Although modern times call for modern looks, architects tasked in designing various structures in UST should always look back to UST’s roots for inspiration, as some of old architectural elements should be preserved.

Intramuros is a good model for invoking the spirit of the Spanish houses and establishments, the guards wearing the uniform of the old Spanish guardia civil, and the history of the Walled City itself give a unique feeling that no other place in the world could probably offer. The sight is a panacea to the disastrous urban planning in the metro.

Although my qualms are a bit too late, I just hope that the next structures to be built in UST will place more consideration to the architectural elements that gave UST its distinction: the complex base of the columns, the raw concrete exterior, moldings, and cornice. By that time, UST will finally have the best grasp on its own trademark and can more effectively convey its more than 400 years of rich history.

I am neither a student nor alumnus of the UST, but I agree with you. The importance of architectural consistency in all buildings of the University must be considered. After all, as you’ve said, “UST will finally have the best grasp on its own trademark and can more effectively convey its more than 400 years of rich history.”