APPROXIMATELY half of the lawmakers in the last three Congresses were preceded and succeeded by their relatives, research by the Varsitarian has found.

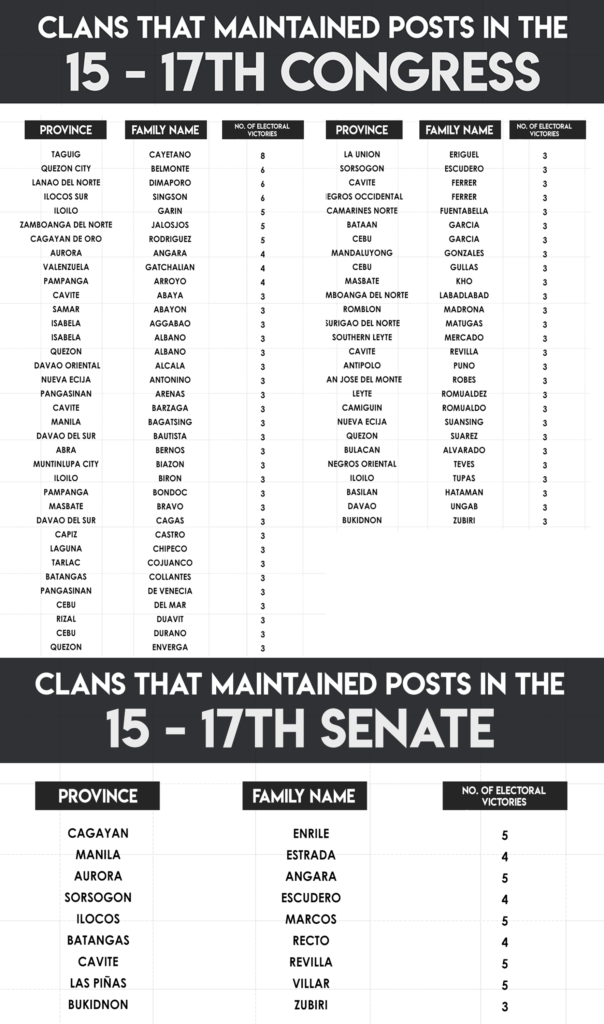

There have been 85 political families whose names have been in and out of the Congress since 2010. Seventy-two families have lorded it over in the House of Representatives, and in the Senate, 13.

“Not one legislation can save it,” Edmund Tayao, political analyst and political science professor in the Faculty of Arts and Letters, said in an interview. “It is a problem of our [current political] system [and landscape].”

“Not one legislation can save it,” Edmund Tayao, political analyst and political science professor in the Faculty of Arts and Letters, said in an interview. “It is a problem of our [current political] system [and landscape].”

Tayao noted the passage of the Sangguniang Kabataan Reform Act of 2015, the first law in the country with an anti-dynasty provision, but said it was not enough change the system.

The Sangguniang Kabataan or youth council reform, under Republic Act 10742, prohibits the election of a member related to any official in the local government within the second degree of affinity.

Dennis Coronacion, chairman of the UST political science department, said an anti-dynasty law could help in promoting a healthy democracy because it goes against the “principle of democracy that everyone should take turns in governing.”

“If we’re just going to undertake the right reforms needed in legislation, I think we’ll be able to reduce political dynasties in Congress, in the local offices,” he said.

Calling dynasties a “tradition,” Coronacion said inheriting a government office was not new and could be hard to eradicate.

“[Political dynasties] are not contributing to the development of democracy. If you want a healthy democracy, then you should do away with the existence of political dynasties,” Coronacion said.

According to a 2016 study by Ronald Mendoza, Ateneo School of Government dean, about 70 percent of the 15th Congress came from dynasties and dominated major but weak political parties.

“This concentration of power by political dynasties produces a non-competitive political system and, in some cases, underpins the restraints, if not the mechanisms for reversals, on growth and equity-enhancing as well as poverty-reducing reforms.” Mendoza said.

Coronacion said the continuous dominance of political families in the two houses of Congress could be attributed to the lack of competent political parties.

“Kasi if the criterion for [the nomination of the candidate] happens to be `yung membership in the family, it’s really a bad way of choosing our government leaders kasi it’s not based on competence. It’s based on blood ties.”

Political parties that nominate candidates do not have a proper vetting process, Tayao said.

“You can’t really expect good candidates or qualified candidates to run for office. Either they are scions of a political family or very popular political personalities or, not even political personalities, but media personalities,” Tayao added.

One of the oldest political names is the Osmeña family. Former president Sergio Osmeña, who was a lawmaker during the First Philippine Republic in 1899, was the first to build a dynasty. Tomas Osmeña was elected in the 15th Congress as 2nd district representative of Cebu. Two Osmeñas have been elected senator after the Marcos regime: John Osmeña and Sergio Osmeña III.

The Aquinos have a long staying power in Congress, with members of the family elected 13 times in different periods in the history of Congress. Sen. Paolo Benigno “Bam” Aquino IV was elected senator in the 17th Congress.

Unhealthy for democracy

Coronacion said it was unhealthy for a democracy to have political dynasties because there was “no level playing field” for other leaders to secure seats in Congress.

“If you’re an ordinary person and you’re up against a political family, medyo lugi ka kasi they have all the resources and you don’t have what they have. So, kung mananalo ka man, there is a remote possibility,” he said. “In other words, it goes against the principle of democracy that everyone should take turns in governing.”

Cleve Arguelles, chairman of the UP Manila Political Science department, said that if the same people get elected or run for office, others would be crowded out.

“Once elections are no longer competitive, political dynasties are no longer incentivized to respond to the interests or demands of the electorate so it also distorts the quality of representation,” Arguelles said. L.C. L. PENERA

To investigate and expose unspoken issues and anomalies, send confidential news tips to the Special Reports team of the Varsitarian at specialreports.varsitarian@gmail.com or at THE VARSITARIAN office, Rm. 105, Tan Yan Kee Student Center, University of Santo Tomas, España, Manila.